In April 2016 Royal Dutch Shell became the first United Kingdom-incorporated oil, gas or mining company to submit its report to the UK company registrar Companies House under the UK’s 2014 Reports on Payments to Governments Regulations (as amended 2015). Shell’s report discloses details of payments made in 2015 to government bodies in 24 countries amounting to $21.8 billion. Shell’s first mandatory payments report marks a major new stage in the global campaign for extractive industry transparency and accountability, and an important step forward for open data corporate disclosure.

Shell’s global footprint

It is encouraging for transparency campaigners to see Shell report under the new UK mandatory transparency regime. Shell’s 2015 report differs from its previous voluntary disclosures by including for the first time, as required by EU and UK law, disaggregated project-level data (which it previously argued against) and by reporting on payments of €100,000 or more made in every country where it operated during the year, including China and Qatar (where it formerly claimed reporting might be problematic for legal reasons).

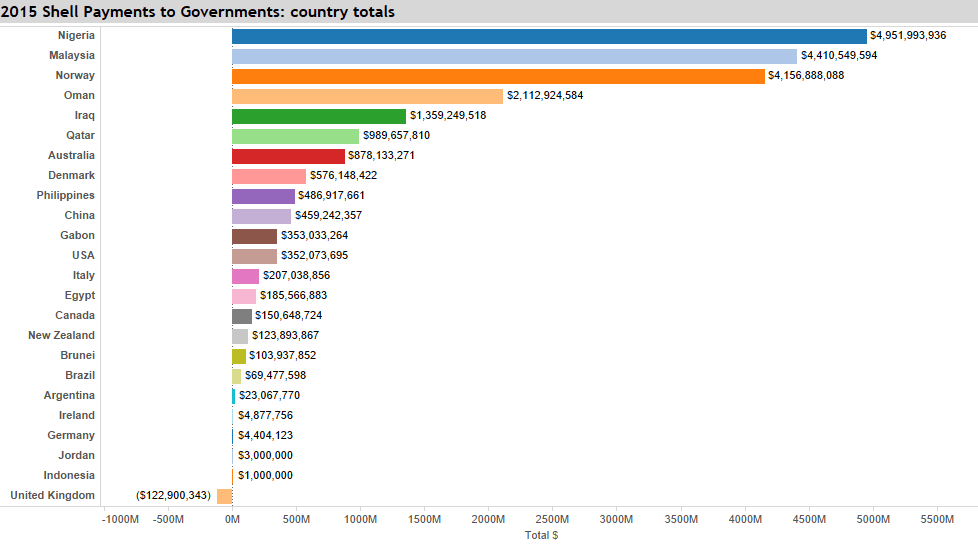

Initial analysis of the size and distribution of Shell’s payments by country helps reveal the company’s global footprint:

The rest of this blog considers the importance of open data in making payment reports such as Shell’s more accessible and useful to citizens and civil society, and suggests a few questions potentially worth pursuing.

Open data

Besides reporting in a conventional pdf format document on its own website, Shell has provided the payment information in open data format using the UK company registrar’s XML schema. Open and machine-readable data reporting under the UK regulations enables the public to export the data in four zipped CSV files for analysis (more on CSV/Comma Separated Values files here).

Shell is the first extractive company to disclose its payments to governments in compliance with the UK’s open and machine-readable data reporting requirements. Statoil (Norway), Total (France) and Tullow (UK) all published their payments to governments in March 2016 but not as open data. The UK Department for Business, Innovation & Skills (BIS) imposed the open data reporting requirement for UK-incorporated companies as a result of advocacy led by PWYP.

The rationale for open, machine-readable extractive industry data was recognised by the G8 countries in their 2013 Open Data Charter:

“Open data sit[s] at the heart of this global movement [for “more accountable, efficient, responsive, and effective governments and businesses”] … [P]eople can use open data to generate insights, ideas, and services to create a better world for all … Open data can increase transparency about what government and business are doing … about how countries’ natural resources are used, how extractives revenues are spent … All of which promotes accountability and good governance, enhances public debate, and helps to combat corruption.”

London Stock Exchange-listed extractive companies that are not UK incorporated, such as Gazprom, Glencore, Rosneft, Sinopec, Statoil and Total, are currently exempt from the UK’s open data reporting requirement. But this will change for financial years starting in 2016, in line with the UK’s current consultation (see PWYP UK’s response here) and third OGP National Action Plan (2016-18). Colleagues at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) have, however, rendered Total’s payment report on 2015 into open data here and provided a handy visualisation.

Using the data files

Three of Shell’s four open data CSV files – “government payments”, “government totals” and “project payments” – identify the country where payments were made (using World Bank country codes). After uploading any of these three files into a Google spreadsheet, as done with “project payments” here (Insert – New sheet – File – Import – Upload), a pivot table can be produced (Data – Pivot table – Report Editor – Rows – Add field — CountryCodeList – Values – Add field – Amount) to highlight the total amount of payments for each of the 24 countries where Shell has reported: see Pivot table 1 (full country names added in column C).

The pivot table can be copied and sorted to produce a ranked list of where Shell made its total government payments in 2015 (Report editor – Order: Descending – Sort by: SUM of Amount). Pivot table 2 clearly shows that Shell’s largest total payments in 2015 were made to Nigeria (US $4.95 billion), Malaysia ($4.41 billion) and Norway ($4.15 billion), followed by Oman and Iraq. The UK, at the foot of the table, was the only country where government bodies made an overall repayment to the company ($122.9 million). The table can be turned into a visual chart like the one above (in this case by exporting the data into https://public.tableau.com/s).

Payments can be further analysed, for example to reveal which government body received most payments during the year. Shell’s “government payments” CSV file results in Pivot table 3, where the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation tops the list, having received $3.607 billion or 16.52% of Shell’s total payments to governments in 2015. The US Internal Revenue Service comes at the foot of the list, having repaid $237.7 million to Shell in taxes.

We can also rank projects by size of payments. Shell’s “project totals” CSV file produces Pivot table 4, where MY15001 / Sarawak Oil and Gas in Malaysia turns out to be the project generating most payments ($3.611 billion or 16.54% of the total).

Further questions

These and other questions arising from Shell’s disclosures will be of interest to civil society in the weeks and months to come.