A few days ago, Moore Stephens submitted the final version of Malawi’s first Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative report to the Multi-Stakeholder Group. This means I have had a chance to already read through the first report and decided over the next month to share 10 things I learned, 10 recommendations made and 10 questions I have about Malawi’s extractive industries governance, which covers forestry, mining, oil and gas. A shout out to Moore Stephen’s Ben Toorabally and Rached Maalej for their input.

To kick it off, here are ten things I think are most important to know for the many people who do not have time to read the 100-page report, and perhaps these will encourage a few more to browse through the first report. I intentionally leave out most recommendations and queries I have that will follow in subsequent articles. All charts and diagrams are from the report, but infographics will follow.

One: What years were covered?

The reporting period covers 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015, which may seem a little behind, and definitely points to the importance of having EITI mainstreamed. This means revenue payments and subsequent allocation of funds from the sector should be processed through an electronic system and these records then can be verified and available online periodically or in real time – useful for both the public and government departments. Right now, a paper-based system is used and the report indicates that receipts were found without information detailing the type of payment and mistakes/different spellings for the same company, and sometimes no name was written down on a receipt making it hard to track revenue. More about areas to improve next time.

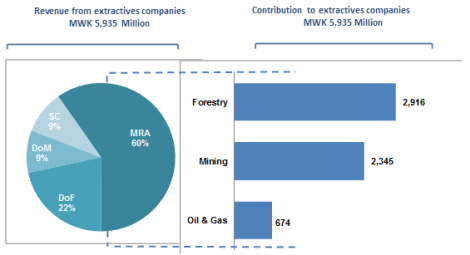

Two: How much money did the extractive industries generate for government?

The total revenue for the extractives was MWK 5,935 million (equivalent to USD 13.6 million). 49% from forestry, 40% from solid minerals, and 11% from oil and gas. This is 0.9% of GDP, 1.1% of government revenues, and 0.6% of exports. The top five companies in terms of revenue were: Raiply Malawi, Paladin Africa, Shayona Cement, RAK Gas MB45, and Vizara Plantations. And the largest revenue stream was Value Added Tax.

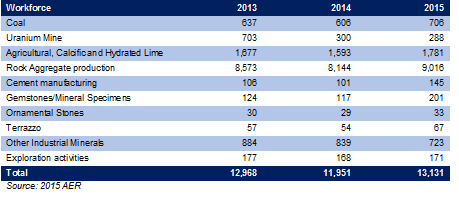

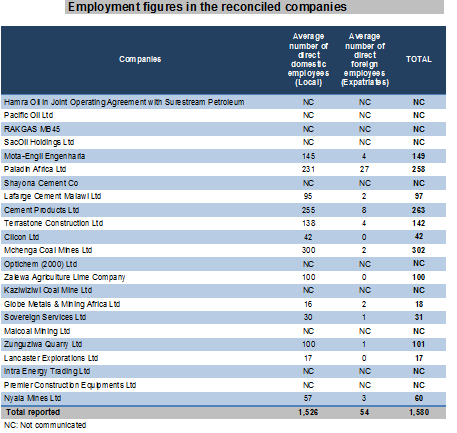

Three: How many people are employed in the mining sector?

13,131 people were working in the mining sector making up 0.2% of Malawi’s workforce. The companies that reported indicated that they employ around 1,526 Malawians and 54 foreign employees.

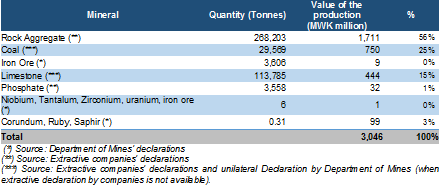

Four: What minerals were produced and exported?

Rock aggregate, coal, and agricultural lime were the top three minerals in volumes produced and value. Most exports were in the region apart from Thailand which was the country of destination for Nyala Mines’ corundum, and some samples were sent further afield to laboratories for testing.

Five: What mining and petroleum prospects exist for Malawi?

During the period, 10 mining licences were awarded and 38 exclusive prospecting licences for solid minerals. The report highlights some prospects for mining, including: the government negotiated an agreement, yet to be signed, with Globe Metals & Mining for Kanyika Niobium Project and the company is exploring for graphite, as is Sovereign Metal. Mkango is at feasibility stage for its rare earths project in Phalombe, while there is another potential rare earth site at Kangankunde, Balaka, but a legal dispute is preventing further development. Another rare earth project has also been at standstill over disagreements with citizens in Mulanje. Cement Products Ltd is to start producing clinker from limestone in Mangochi for cement and Shayona Cement Corporation is doing the same in Kasungu, while Bwanje Cement is looking for financiers for its project in Ntcheu. A couple of coal mining projects in the north face challenges because of cheaper coal imported from Mozambique.

During the reporting period, oil exploration was put on hold as government investigated the licences, contracts, and licence holders. The suspension was lifted in 2016. Petroleum exploration in Lake Malawi National Park, a World Heritage Site, remains highly contested and government has been asked by UNESCO not to explore in the area or a buffer zone.

Six: What do we learn about forestry?

Malawi used to have the largest man-made forestry in Southern Africa (Chikangawa), but today most of the twenty fuelwood/poles and timber plantations managed by the Department of Forestry (about 90,000 hectares) are degraded. Forestry resources across the country are depleting rapidly (2.6% per year) given the reliance on fuel wood and the expansion of agricultural land. Raiply Malawi has had a 60-year concession since 2009 to manage 20,000 hectares of Viphya Plantations, the largest of five agreements.

Seven: Which companies did not comply?

Eight companies from the 23 chose not to report (or possibly were too late?) – mining companies Shayona Cement, Kaziwiziwi Coal Mine, Intra Energy Trading, Malcoal Mining, and Premier Construction Equipment, along with Hamra Oil, Pacific oil and SacOil Holdings which all hold oil exploration rights did not comply with MWEITI. Artisanal and small-scale mining has not been included at this stage.

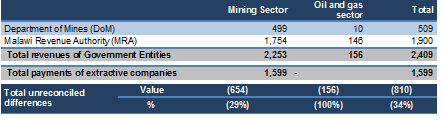

Eight: What was the difference in revenue data reported by government and companies?

The main work of the Independent Administrator was to reconcile payment information to government that was submitted by companies with government receipts submitted by the MRA and Department of Mines (the Department of Forestry was not included in the reconciliation). There was a difference of 34% between the amount government declared as having received and the amount companies reported. Most of the difference was because of the aforementioned non-compliant companies.

Nine: Are contracts publicly available?

Contracts for the extractive sector are in the public domain, but the contract awarding process faces some challenges in terms of transparency and procedure. The government has signed two agreements for mining (one with Paladin for Kayelekera uranium mine in Karonga and another with Nyala for a Chimwadzulu ruby mine in Ntcheu), three for petroleum (two productions sharing agreements with RAK Gas MB45 and one with Pacific Oil) and five in forestry and over 120 co-management agreements with communities near forest reserves.

However, there is no model agreement for mining, petroleum or forestry contracts which means the terms vary from one contract to another and are not always aligned with rates defined in legislation. This often lead to non-relevant terms being negotiated and could encourage corruption. Some companies reported their legal owners, but beneficial ownership will be fully implemented as part of the initiative by 2020.

Ten: What progress is government making?

It’s important to note steps the government is taking to reform the sector for investors and to improve returns for Malawi through the domestication of the Africa Mining Vision and the Malawi Mining Governance and Growth Support Project, financed largely with a World Bank loan. This includes reviewing mining legislation with a provision for community development agreements and developing an artisanal and small-scale mining policy, upgrading the mineral licencing systems with a cadastre, strengthening monitoring of mineral operations, reforming the tax regime, building the capacity for tertiary education, and establishing a modern geo-data centre. The recent airborne geophysical survey is being followed up by exploration activities to improve knowledge about our resources.

Take a look at Malawi’s first EITI report here.

I look forward to your feedback!

A version of this will appear in the May edition of the Mining & Trade Review.

This is part of a project I am doing as Publish What You Pay Data Extractors.

*This blog was first published on mininginmalawi.com